What Does Accountability Look Like?

As an administration ends, there’s plenty that cries out for justice — but scarce time and resources require setting priorities

Good evening. Voting in the 2020 presidential election ended 43 days ago. The inauguration happens in 35 days.

The Latest

moral hazard (n.) – the lack of an incentive to avoid a given behavior when one has protection from consequences for it.

“We want them infected.” A White House advisor reportedly said those words this summer, urging his colleagues to adopt a herd immunity approach to fighting — more accurately, toward accommodating — the coronavirus.

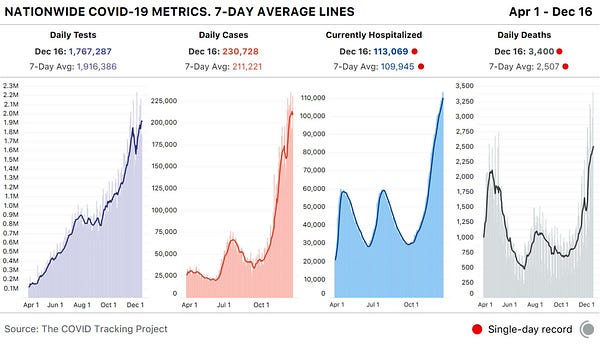

As we approach the year-end holidays, the death toll of the coronavirus pandemic in the U.S. has spiraled above 300,000. Jobless reports have ticked upward again as infection rates climb all over the country. Millions of the long-term jobless are nearing the limit of their unemployment benefits — although as I type, negotiators in the Capitol appear to be nearing a miserly, but desperately needed agreement on relief.

Conditions are tough, in other words. I’m hard-pressed to think of a time in my life when the words “joy to the world” have felt more discordant. Yet those words might be dancing through the heads of associates of the outgoing president — who, according to a CNN report today, might be disposed to hand out pardons as if they were party favors:

This is a juxtaposition that can make one paralytic with rage — but for the moment, I’ll use it to ask a question: what should accountability look like?

My bottom line is the same as that of Eric Schultz, who worked as a White House deputy press secretary during the Obama administration.

Retribution means nothing to me as a principle — but punishment matters. A culture in which people can amass riches or power by doing bad stuff, and never face accountability, is one whose commanding heights will eventually fill with people who do bad stuff. (A version of this is arguably playing out with companies such as WeWork and Uber.)

Come January, however, the Biden administration will have a raging pandemic to bring under control, a vaccine rollout to execute, an economic calamity to redress — and the possibility, to top it off, of a Republican-controlled Senate standing in the way. Justice matters, but the time and attention for multiple open-ended investigations probably won’t exist.

This mismatch between task and resources probably puts comprehensive scrutiny of the Trump administration’s lawlessness off the table. Justice circumscribed, however, is different from justice denied — and three simple principles may help to resolve the tension between the calls for accountability and the need to focus federal resources elsewhere.

1. There must be a look back

Kevin Kruse, a history professor at Princeton, put this well in a piece for Vanity Fair about an inquiry into a different national calamity, the Great Depression:

If Democrats actually want to move on from the Trump era, they’ll first have to provide a real reckoning with the past. Not everything can be probed, of course. But a deep dive into the administration’s mishandling of the coronavirus and other crises, plus its wider pattern of incompetence and corruption, would be warranted. … Policies follow politics, and before any administration can “move forward,” it first has to make clear what it’s moving forward from, and why. Leaders have to tell a story before they turn the page.

With Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell already maneuvering to blame Biden for economic woes while insisting on economic austerity likely to make such woes more protracted, it may be crucial for Biden’s political fortunes to show Americans how the Trump administration botched the response to the pandemic — and why its policies bear direct responsibility for our current messes.

2. There is a great deal to account for — but we have to pick

Over the summer, Josh Marshall of Talking Points Memo wrote of the vast, still unmapped sprawl of the president’s corrupt acts — and suggested that the imperative of exposure outweighs the need to punish.

We simply cannot move forward as a society or a political system without a thorough accounting of the totality of what happened during this unparalleled era of lawlessness, corruption and misgovernance. … [But] prosecutions frequently work at cross purposes with disclosure and full accounting for public wrongs … [and] a full accounting of what has happened is more important than judicial punishment for individual wrongdoers. Accounting should be the first priority and we should pursue it even at the expense of criminal prosecutions.

That’s tough medicine for me. As Marshall rightly pointed out, though, one can’t prosecute Trump or his staffers for wrongdoing “before you even know what the something is. And the reality is that so much remains hidden that we don’t really know even what’s happened.”

Yes, Trump has committed plenty of wrongful acts in public. But one can make a compelling argument that his brazen conduct hints at the scope of what we may not yet know. Finding out will likely prove worth the effort.

3. We need a rubric for deciding where to focus

James Fallows, a longtime writer at The Atlantic who served as a speechwriter for President Jimmy Carter, wrote a lengthy piece last week to suggest a framework for sorting through the rubble of the Trump years and determining what deserves future scrutiny.

Halting the corrosion is the very least that needs to be done—equivalent to stabilizing the patient. Just as important, investigations should be conducted into three catastrophes during the Trump years that have undermined our health as individuals, our morality as a people, and our character as a democracy.

To this end, Fallows proposes commissions of inquiry into three matters, each of which symbolizes broad patterns of destructive behavior: the lethal handling of the coronavirus pandemic, the human-rights trampling child separation policy, and Trump’s efforts to undermine democracy itself. Triage, argues Fallows, compels narrowing the official focus to a handful of wrongs — in order to make the country “face its failures squarely and through a common lens,” yet preserve the new administration’s “limited time and political influence.”

Fallows points out that Trump can already count on attention to past bad acts, courtesy of state and local prosecutors — who in New York, at least, are already tracking chicanery at Trump’s companies. For matters such as that, the best course Biden can follow involves merely staying out of the way.

We don’t yet know, at this writing, who Biden will nominate for attorney general — but a part of Fallows’ essay crystallized a case that’s rattled around my mind for choosing outgoing Senator Doug Jones, of Alabama:

Biden needs to select an attorney general who will be seen as the most principled and eminent of all his Cabinet members, and choose correspondingly strong and independent inspectors general for the executive departments. The rest is up to them.

Jones has spent much of his career as a prosecutor. I’ve known that for a while as a native of Birmingham, Ala., where Jones prosecuted the white-supremacist bombers of the 16th Street Baptist Church. The moral authority conferred by closing that cold case, and the transpartisan good indicated by his ability to win a Senate election in Alabama, suggest — to me, at least — the eminence that serving atop the Justice Department, while providing the appearance of impartial, fair leadership of future investigations, will require.

Like I said, we don’t know who Biden will pick. But he could do far worse.

In the Conversation

Noah Weiland, at The New York Times: “‘Like a Hand Grasping’: Trump Appointees Describe the Crushing of the C.D.C.”

“Often, Mr. McGowan and Ms. Campbell mediated between [CDC leader Dr. Robert] Redfield and agency scientists when the White House’s guidance requests and dictates would arrive: edits from Mr. Vought and Kellyanne Conway, the former White House adviser, on choirs and communion in faith communities, or suggestions from Ivanka Trump, the president’s daughter and aide, on schools. ‘Every time that the science clashed with the messaging, messaging won,’ Mr. McGowan said. … Episodes of meddling sometimes turned absurd, they said. In the spring, the C.D.C. published an app that allowed Americans to screen themselves for symptoms of Covid-19. But the Trump administration decided to develop a similar tool with Apple. White House officials then demanded that the C.D.C. wipe its app off its website, Mr. McGowan said.”

Jonathan Rauch, at The Atlantic: “What Trump Has Done to America.”

“The country now has not just two political parties but two political regimes, one nomocratic and the other teleocratic, cohabiting but incompatible. The closest modern parallel might be the South in the days of Jim Crow. Ostensibly, the South was part of American democracy, but in reality it was a separate polity—undemocratic because so many voices and voters were excluded, teleocratic because its permissible outcomes were bounded by white supremacy. … That arrangement, of course, proved not only unfair but unsustainable. Trump’s reorientation of the GOP as the party whose guiding principle is ‘Heads we win, tails you lose’ is likewise unfair and unsustainable.”

Adrienne LaFrance, at The Atlantic: “Facebook Is a Doomsday Machine.’”

“The rise of QAnon, for example, is one of the social web’s logical conclusions. That’s because Facebook—along with Google and YouTube—is perfect for amplifying and spreading disinformation at lightning speed to global audiences. Facebook is an agent of government propaganda, targeted harassment, terrorist recruitment, emotional manipulation, and genocide—a world-historic weapon that lives not underground, but in a Disneyland-inspired campus in Menlo Park, California.”

Jill Colvin and Jonathan Cooper, at the Associated Press: “Trump Voters Accept the Biden Election ‘With Reservations.’”

“Republicans across the country — from local officials to governors to Attorney General William Barr — have said repeatedly there is no evidence mass voter fraud affected the outcome. … Still, coming to terms with this pile of evidence has been difficult for many Trump voters. They expressed disbelief that Trump could have lost, given the huge crowds he drew to his rallies. Some said their suspicions were heightened by the mainstream media’s reluctance to air Trump’s baseless claims. And they repeatedly pointed to the slower-than-usual vote count as evidence something had gone awry. ‘Something’s not right here,’ said [Robert] Reed, who lives in East Lampeter Township [in Pennsylvania].”

David Dayen, at The American Prospect: “Joe Biden Is Unhappy About the Day One Agenda.”

“Biden is not creating an administration with any visible intention to be creative about executive authority. The past several Cabinet selections, including Pete Buttigieg to run the Transportation Department, have not installed people with deep knowledge of the federal bureaucracy and the authorities buried in statutes that can assist them. Inexperience can be overcome, but if the executive branch is the only path forward for progress, you’d want people who know something about the agencies they will lead.”

Matthew Yglesias, at Slow Boring: “America’s Amateur Government.”

“Unfortunately it’s a little bit hard to know how to pull out of the spiral that we are in. … I hope the smart conservatives and libertarians who are into governance quality and state capacity can convince their friends in GOP politics that this stuff is important. But it still looks to me like they are on a level where if you think that regulation is bad, then you should want regulatory agencies to be low-prestige, low-paid work with little status and if that means they do a bad job then it just proves you were right to begin with.”

Sherrilyn Ifill, speaking with Anand Giridharadas at The.Ink: “Justice and Accountability After Trump.”

“There just has to be a reckoning. There just has to be. You can't reset unless you truth-tell and demand that people are held accountable for what they have done. And if they've broken the law, they should be held accountable for breaking the law. To the extent that they've broken norms, ethics, values, they should also be held accountable for that.”

Biden Hires and Appointments

Former Mayor Pete Buttigieg, Secretary of Transportation

From the Biden-Harris transition team: “Pete Buttigieg served as the 32nd Mayor of South Bend, Indiana, for eight years. With bold thinking and innovative leadership, Buttigieg revitalized a city that had been struggling for decades after the Studebaker auto company collapsed and was once called one of America’s “dying cities.” He brought South Bend back from the brink, creating thousands of jobs and spurring local investment during his tenure. His “Smart Streets” initiative helped change the fortunes of downtown South Bend — revitalizing the city, redesigning the streets, and bringing in major economic investment.”

Two Moments of ‘Huh?’

Some people can see the darndest things.

Speaking of what people see: I don’t know about you, but when I looked at this rendering, I … I did not see a banana.

That’s all for this issue. See you on Friday.

American Interregnum is a pop-up newsletter covering the issues and ideas that will define the Presidential transition period from Nov. 3, 2020, through — we’re all but sure now — Jan. 21, 2021. It is written and edited by Justin Hendrix, Greg Greene, and Melissa Ryan. Have questions or comments? We love your feedback. Reply directly to this email. We read all responses and respond to most.

Did someone forward you this email? Don’t forget to subscribe: